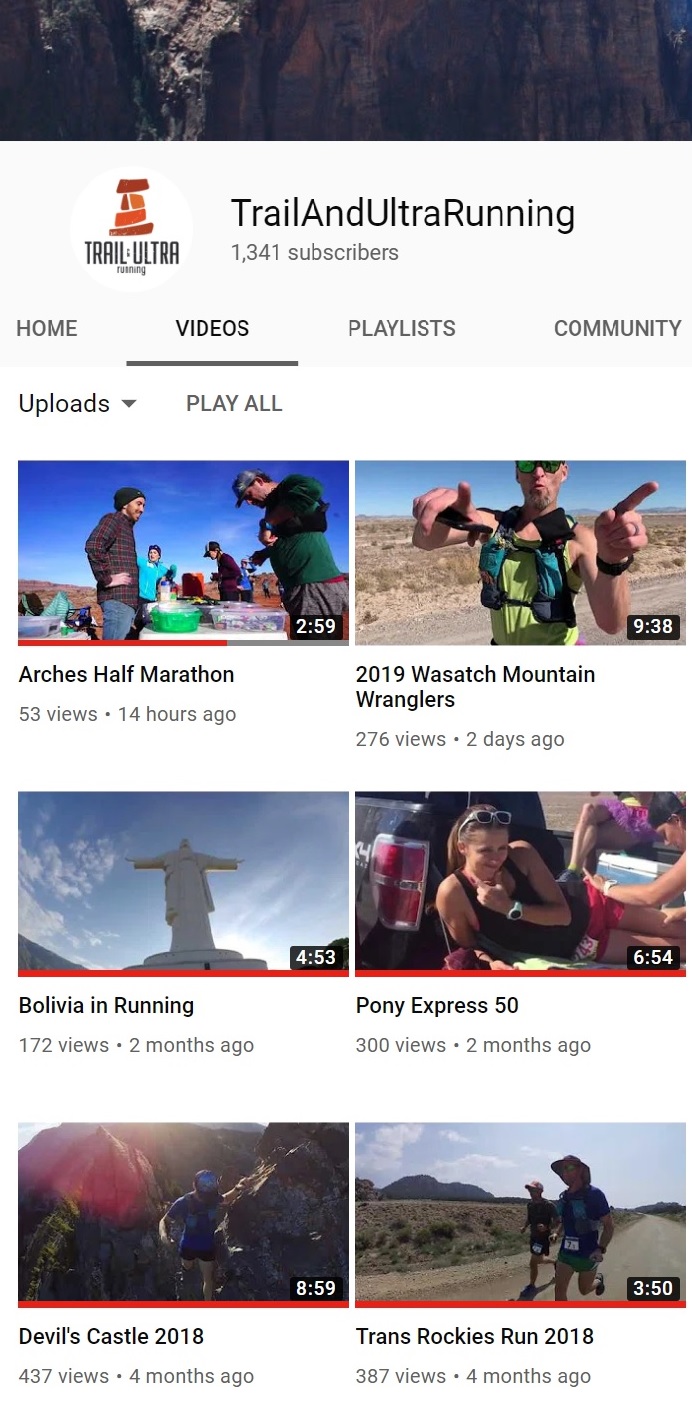

Two weeks ago I went to Wyoming to pace and support John La Croix (aka Sherpa John) in the Big Horn 100M. Jeremy was the other pacer/crew member for John, and our friend Mark was the other runner attempting to finish his first 100M race.

At check-in I stood in front of the map table listening to a weathered trail runner named Wendell discuss in minute detail every square inch of the mountain. Crews, pacers and runners learned about elevation changes, exposed places where the wind would whip, where the run-off had saturated the ground and how to layer appropriately. I listened intently and tried to memorize the information and let it seep into my brain.

At dinner that night and later, around the campfire, Sherpa John explained his gear and what he wanted at each Aid Station. He had a binder prepared with instructions for every change and I read through it slowly.

Two small groups of runners joined us at the campfire that evening and we made new friends. It was an enjoyable evening of laughter and stories, though we all turned in early. A runner respects the distance and this was no exception.

In the morning we headed to the pre-race meeting in Dayton, WY, held at the park that would ultimately be the Finish Line. Runners with huge quads and runners with tiny calves stood quietly. Within minutes most people sat motionless on the grass. Not an ounce of energy would be expended before it was time.

I listened intently to the explanation of the terrain once again. This time I was able to visualize the aid stations and each turn, as well as the water crossings and the open places where we would be exposed during my stint as pacer from mile 30-49. At mile 49 Jeremy would take over and accompany Sherpa John back to mile 66, where I would then jump in and take another 16-mile leg. Then Jeremy would finish out the run in the late morning/mid-afternoon.

After the pre-race meeting we slathered sunscreen, checked water bladders, added electrolytes, then double and triple checked everything. Our two runners were ready. Mark would go solo on his first attempt at a 100M race. Jeremy and I hoped to be at the aid stations when he came through to offer assistance, but our first duty was to Sherpa John.

We drove to the start line and cheered heartily as the 100M runners took off. Then Jeremy and I went back into town to find food. Sherpa John wouldn’t come through the Aid Station for at least three hours. Time to eat.

After lunch we loaded up the cooler with ice and a few items from the convenience store. Sherpa John mentioned how much he loved grilled cheese sandwiches; Jeremy and I wanted to surprise him with his favorite trail food. I had a pan and Jet Boil fuel in my camping gear so we picked up a loaf of bread and sliced cheese to go with the pats of butter I pocketed from the restaurant.

[Continue Below]

[tabs slidertype=”images” auto=”yes” autospeed=”4000″][imagetab width=”558″ height=”372″]http://trailandultrarunning.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/lara-robinson-pacing.jpg[/imagetab][imagetab width=”558″ height=”372″]http://trailandultrarunning.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/lara-robinson-pacing-ultra-marathon-prep.jpg[/imagetab][imagetab width=”558″ height=”372″]http://trailandultrarunning.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/lara-robinson-pacing-ultra-marathon-shoes.jpg[/imagetab][imagetab width=”558″ height=”372″]http://trailandultrarunning.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/lara-robinson-pacing-ultra-marathon-big-horn-course.jpg[/imagetab][/tabs]

A pacer needs to understand how much driving might ultimately be involved in supporting a runner on the course. Before the race I printed out directions to each of the Aid Stations. I did not read them, however, for the simple reason that they made my head spin.

To Footbridge Aid Station in the Little Bighorn River Canyon: From Dayton, cross the Tongue River Bridge at the eastern aspect of town and turn north on Wyoming Hwy 343 proceeding 5.2 miles to the intersection of Wyoming Hwy 345 (old US Hwy 87). Turn left on Wyoming Hwy 345 and proceed past Parkman, WY, going into Montana at 5.9 miles where you enter the Crow Indian Reservation and continue on this highway until you reach the Littlehorn Road just south of Wyola, MT, at 15 miles. Turn left on the Littlehorn Road, cross the railroad tracks and proceed west on the Littlehorn Road toward the Bighorn Mountains crossing the Little Bighorn River at 9.7 miles, having the pavement change to gravel at 10.5 miles, crossing the Little Bighorn River at 12 miles, and encountering a cattle guard at a 4-way junction at 15.85 miles. The 4-way junction has a sign by the cattle guard erected by the Wyoming Game and Fish Dept which is brown stating the road going past the cattle guard provides public access through private lands, please stay on established roads. Proceed through the cattle guard, taking this primitive road into the mouth of the Little Bighorn River Canyon. You will ford a creek at 0.45 miles, ford a second creek at 0.6 miles, reenter Wyoming at a primitive sign noting that you are at 45 degrees Latitude, and cross the Little Bighorn River on a bridge at 1.5 miles. Continue on the northern side of the Little Bighorn River where you will encounter an area where we wish crews to park at approximately 2.5 miles. Be careful not to block the road when parking and do not block the private bridge crossing to the cabins on the south side of the Little Bighorn River when parking in this area. Park well off the road; but be careful you don’t high center your vehicle on scattered rocks in this parking area. Parking is very limited further up the canyon and is reserved for aid station/emergency access vehicles. After parking, proceed by foot approximately ¾ mile distance from the designated parking area up the canyon on the primitive road to reach the Footbridge Aid Station. You will go past the Wyoming Game & Fish Patrol Cabin area shortly before you encounter the Footbridge Aid Station.

Jeremy navigated while I drove. We found the Dry Creek Aid Station after a few wrong turns and jogged from the car to the tent where Sherpa John was waiting. He had arrived a few minutes earlier and stood munching a sandwich. We refilled his hydration pack with electrolytes and tucked Gu’s into his belt, reapplied sunscreen and sent him on his way.

At this point we picked up Nick, a guy whose runner was matching Sherpa John’s pace very closely. We arranged to carpool into the next Aid Station due to the ruggedness of the terrain and the fact that his car might not make it over the three washes we’d encounter on our way to the 50k Aid Station.

Sherpa John came into the Footbridge Aid Station at 6pm on the nose. We were pleased with his pace and progress. Jeremy cooked up the sandwich while I finished getting my own gear ready for a 20-mile jaunt on the mountain. A few minutes later we hit the trail.

The course winds up the mountain in this leg, gaining approximately 5000’ in elevation over a steady 18-mile climb. We decided to hike the inclines and run the flats and downs. This would save energy and keep a steady pace.

I led the way for a while and set a moderate pace, looking over my shoulder frequently to make sure I didn’t drop my runner. After a while we told stories and Sherpa John lead the way. We passed through several small Aid Stations where we grabbed calories, adjusted clothing, popped electrolyte tabs and used the bushes.

I’ve hung around ultra runners long enough to know how fatigue affects decision-making skills. A pacer needs to be ready to tell a runner what to do, when to do it, and watch for adverse changes. Before the race Sherpa John reiterated what others have said; it doesn’t matter what you say, as long as you say it with a positive attitude. Lie if need be; tell the runner how great he’s looking even if you think he might be on death’s door. Pull the guy through. That’s the pacer’s job.

At the 66-mile Aid Station we waited for Sherpa John in the pre-dawn light. He was moving slowly according to Jeremy’s updates via walkie talkie. The last four miles to the Aid Station took two hours. Sherpa’s feet were trashed after being soaked for nine hours. He changed his socks on the mountain after getting through the worst of the run-off, but the moisture inside his skin caused blisters and a cavernous split on the bottom of his foot.

At the Aid Station he joined a group of runners huddled around the campfire. I took my crew duties seriously and flew into action getting wet socks and shoes off to bathe his tired, muddy feet. His skin had to dry out.

Jeremy, Sherpa John and I talked seriously about the remainder of the race and the realistic possibility of finishing based on pace and condition of his feet. After about 40 minutes we all knew what had to happen.

He turned in his bib and we drove out of the Aid Station. His race was over.

The following weekend I headed to Vermont to run the Green Mountain Relay, a 200-mile, 12-person run. Each runner was assigned three legs. I was excited and thrilled to experience a group of firsts: first Relay Race, first time to Vermont, first time meeting the entire team.

About an hour after my first leg a teammate went out for his 8.5-mile run and got into trouble within minutes. The hills, humidity and pace led to vomiting within the first two miles. He’s a strong runner but wasn’t pulling through.

At mile six I jumped in and started pacing him. There was no ASKING if he minded my presence. I explained the plan, made him drink periodically and shake out his arms. He was to match my pace and not go an iota faster. All his decision-making privileges were hereby revoked. His only job was to run.

When we ran up a hill I provided a running commentary (pun intended) of the different muscles being used, how hard to push, and when we got to the top of a hill I chatted about how he needed to relax his hip flexors, drop his shoulders and get air into his diaphragm. I told stories about whatever popped into my head, knowing that it didn’t matter what I said as long as I gave him something to focus on other than his own thoughts.

I paced him for a little over 20 minutes that day; not much in the overall scheme of things. But those 2.5 miles of pacing pulled a teammate through as much as pacing a runner 20 miles in the dead of night. Because of the support he wasn’t trashed and could remain competitive, strong and healthy.

Sherpa John gave me my first experience as a pacer at the Big Horn 100 in Wyoming. It was a privilege and pleasure to be able to support a teammate and friend on a 27+ hour Relay journey through the wilds of Vermont as well.