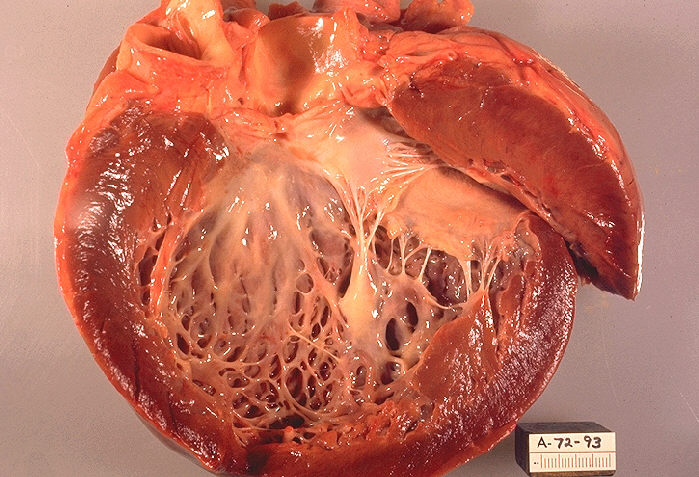

The news that the autopsy of Micah True — the ultrarunner who died recently in New Mexico during what was, for him, an easy 12-mile run — revealed that he had heart disease has been quite a stunner for the running world. True, known as “Caballo Blanco,” had cardiomyopathy, or enlargement of the heart. Specifically, his left ventricle was enlarged and thickened. Of the heart’s four chambers, the left ventricle is the largest and most muscular; its job is to pump blood to all the cells of the body. When the walls of the chamber get too large, however, pumping efficiency is reduced. Further, abnormal thickening of the walls — visible in this CDC photo of a heart with cardiomyopathy (above left) — is associated with development of scarring. This reduces heart elasticity and further impacts functionality. Cardiomyopathy is also strongly associated with the development of abnormal heart rhythms that are incompatible with life, particularly during exertion. In other words, it’s likely that True’s heart became thicker and larger over time until even a routine run resulted in sufficient exertion to make his heartbeat erratic.

Unfortunately for those of us who look at running as a great way to maintain physical and cardiovascular fitness, the science world is increasingly beginning to suspect that it’s possible to have too much of a good thing. A number of studies have shown that a moderate amount of running (or any other form of exercise) is quite healthy and reduces the risk of death from heart disease and other causes (see, for example, Maron et al, Rosengren et al). However, a new study published in the medical journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings suggests that chronic training for ultra-distance events can cause heart thickening and scarring — cardiomyopathy — over time (O’Keefe et al).

It’s difficult, at the present time, to know what to make of this information. After all, the studies of non-runners, moderate runners, and long distance runners that are beginning to make scientists and health care practitioners question the wisdom of year upon year of ultra-distance training haven’t been randomized. That is to say, the studies were done by comparing the health of runners to that of non-runners, but study participants were either runners or non-runners when they entered the studies. Without randomization, it’s possible to say that long term, long distance running is correlated with heart disease, but it’s not possible to say that it causes heart disease. We can speculate about alternatives to a causal relationship; for instance, perhaps those with a family history of heart disease are particularly likely to become runners, hoping that the sport will help to improve their chances of maintaining good heart health. This would mean that among runners, there would be an abnormally large percentage of people with a genetic predisposition to heart disease, and would make the observation that distance runners have more heart disease less remarkable. These speculations aren’t provable (or particularly useful), but they do serve to make the point that we can’t know for sure, on the basis of non-randomized studies, whether chronic training for ultra-distance events negatively impacts heart health. Still, the more these studies begin to pile up over time, the more meaningful the results become, even if they are correlational.

In the end, there are two conclusions that can be reasonably drawn from the amassing research. The first is that running, no matter how much, is better for health than not running. The second is that ultra-distance athletes should probably consider having regular and thorough medical checkups by a health professional who is well aware of the individual’s preferred level of sport participation.

Do you worry about the link between ultra-distance running and heart disease?

References:

Maron et al. Risk for sudden cardiac death associated with marathon running. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996 Aug;28(2):428-31.

O’Keefe et al. Potential Adverse Cardiovascular Effects From Excessive Endurance Exercise. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 June;87(6). Epub ahead of print.

Rosengren et al. Physical activity protects against coronary death and deaths from all causes in middle-aged men. Evidence from a 20-year follow-up of the primary prevention study in Göteborg. Ann Epidemiol. 1997 Jan;7(1):69-75.

What’s up, everything is going fine here and ofcourse every one is sharing data, that’s really good,

keep up writing.